Welcome to Lies Agreed Upon, the podcast that looks at how film and television use history to talk about today.

I’m Lia Paradis

And I’m Brian Crim.

Every one of us tries to make sense of our current world by telling versions of history that seem to put the puzzle pieces together, or offer the most validation. Our own lies agreed upon. In this first season of our podcast, we’ve explored the many ways that 9/11 influenced writers, directors and producers and how they used history to discuss and process that day and its legacy.

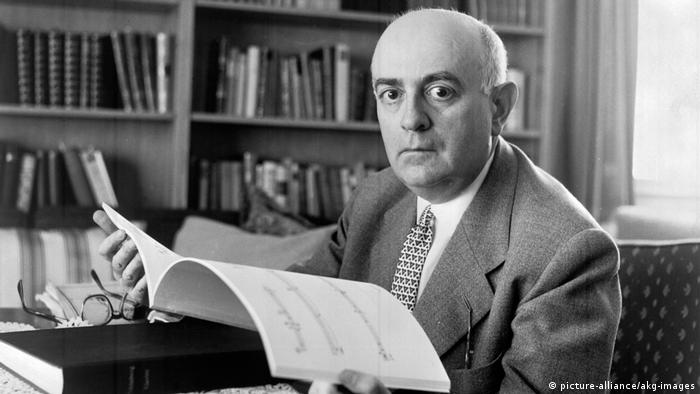

In our final episode we are doing something a little different. Our focus has been on how historical events are portrayed on screen after 9/11 – from Antiquity to 9/11 itself. But we all know the cultural impact of 9/11 went far deeper and extends to every genre and medium of representation. Holocaust scholars speak of a “before” and an “after” when it comes to culture, religion, politics, and philosophy. In a memorable and much cited passage in Cultural Criticism and Society (1949), Theodor Adorno, the eminent German philosopher and founder of the so-called Frankfurt School, wrote: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” What he was really saying is that you can’t return to traditional modes of representation without taking into account the Holocaust. More to the point, it is impossible to avoid.

America’s 21st century began with a trauma, an event that acts a similar “before and after” milestone. As we’ve discussed these past six episodes, Hollywood used history to reflect how the world changed and offer interpretations about 9/11’s causes and legacies. It took five years to address directly the trauma itself, World Trade Center and United 93 for example. But SciFi, and horror for that matter (often the distinction is purely academic), was processing our trauma and representing it unapologetically almost immediately after 9/11. This episode is more of a free-wheeling discussion about movies and tv shows that used the otherworldly to communicate our fear, anxiety, and let’s face it – fascination with the aesthetics of destruction. SciFi has always been political, from War of the Worlds the book, written in 1898, to War of the Worlds the movie (2005 version). And it’s not just 9/11 Sci Fi takes on, but all that came after. Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the national security state, torture and detention, insurgency and counterinsurgency, and fear of the “Other.”

There’s an entire body of academic literature on Sci Fi’s relationship to traumatic events like the Holocaust or 9/11 we won’t bore you with, but I will promote my own book for a second because it did lead me to this topic for Lies Agreed Upon. I wrote Planet Auschwitz: Holocaust Representation in Science Fiction and Horror Film and Television after teaching Holocaust history and cinema courses for many years. I noticed how frequently these genres mined the imagery from both real history and the cinematic Holocaust to represent trauma, horror, grief, apocalyptic ideologies, and the perrenial fear of the return of the repressed. Nazism may be defeated, but how many films and video games tell us otherwise? While researching for the book I noticed more recent examples of this phenomenon of using the Holocaust as fodder for SciFi and horror used 9/11 just as freely, often conflating and muddling the imagery and messaging of both traumas. The Holocaust was the THE STANDARD for representing horror in the modern world – why wouldn’t it be? But after 9/11 there was a new aesthetic standard and they live together very comfortably in some of the shows and movies you love.

What’s really striking is how so many people referenced movies like Independence Day and it’s spectacular destruction of American landmarks just hours after the attack. There simply was no earthly comparison to what we experienced. And we all know terrorism is supposed to be cinematic. Here’s what film critic Neal Gabler wrote a few days after 9/11:

“In a sense, this was the terrorists’ own real-life disaster movie – bigger than ‘Independence Day’ or ‘Godzilla’ or ‘Armageddon’, and in the bizarre competition among terrorists, bigger even than Timothy J. McVeigh’s own real life horror film in Oklahoma City, heretofore the standard. You have to believe at some level it was their rebuff to Hollywood as well as their triumph over it – they could out-Hollywood Hollywood.”

I was in the intelligence community right after 9/11 and one of the big initiatives was for agencies to reach out to Hollywood writers and novelists for ideas on what could be coming next. In other words, actual intelligence experts needed the most far out scenarios laid out for them by people whose job was to imagine the destruction of our society. These Red Team analyses actually made their way to lowly analysts like myself and it became my job to determine if a dastardly terrorist might also be reading Tom Clancy or mimicking something they saw on 24.

But it’s Sci Fi that luxuriates in mass destruction without real consequences. The great Susan Sontag wrote “The Imagination of Disaster” in 1965 to comment on the spate of Sci Fi films dominating the landscape during the atomic age. She believed the whole genre, which became enormously popular after World War II, downplayed the crises plaguing the world, like nuclear destruction, and thereby normalized “what is psychologically unbearable, thereby inuring us to it.” She continues, “Science fiction films are one of the most accomplished of the popular art forms, and can give a great deal of pleasure to sophisticated film addicts. Part of the pleasure, indeed, comes from the sense in which these movies are in complicity with the abhorrent.” She calls Sci Fi the “purest form of spectacle.” After 9/11, Sontag’s essay suddenly started making the rounds again because suddenly the unthinkable became our reality and SciFi wasted no time, as she says, becoming complicit with the abhorrent.

What are some common themes of post-9/11 SciFi? See this article by Annalee Newitz, which informs some of our thoughts below.

The first, and it’s obviously not new but took on greater significance is that New York must be destroyed. We already talked about how Independence Day leveled our landmarks, the Empire State Building in this case, but soon the tri-state area was ravaged again in War of the Worlds (2005), I Am Legend (2007), Cloverfield (2008), the first season of Heroes (2006-07). We can go on and on.

A second theme, fairly new and obviously the result of a post-Patriot Act society, is that the Surveillance State is watching you. Think of Minority Report (2002) another Spielberg, and A Scanner Darkly (2006)

Third, the terrorists are everywhere. Its also ok to dehumanize the enemy and kill them without guilt or remorse. They are beyond Other. It’s not a stretch to see the real terrorists, or anyone who looks like them, as target just enemies to exterminate. Remember the classic miniseries V from the 80s? The reboot in 2009 featured aliens who were organized in underground cells like terrorists. We’ll talk about Battlestar Galactica, which pretty much defines the 9/11 SciFi epic and its debates about terrorism. There’s even terrorists in Star Trek: Enterprise and Harry Potter. They’re everywhere.

Fourth, the national security state is plotting the end of the World. The new slate of agencies charged with ensuring the nebulous and menacing concept “homeland security” quickly turned sinister in our feverish imaginations. In the series Jericho government agencies nuked parts of the US to start a coup. Also, 28 Weeks Later, the sequel to the new zombie classic 28 Days Later, where authorities can’t resist trying to control the virus that took out our closest ally in a month. In the 50s the military and government delivers us from monsters, after 9/11 they are usually unleashing them upon us and covering their asses in the process.

There are many more, and horror is a related genre with some obvious post-9/11 signatures. Kevin Wetmore s’ book on subject is worth quoting:

“One key difference between pre-9/11 and post-9/11 horror is that the former frequently allows for hope and the latter just as frequently does not.

After 911, nihilism, despair, random violence and death, combined with tropes and images generated by the terrorist attacks began to assume a greater prominence in horror cinema.”

Torture porn also became popular – Saw, Hostel, any of the movies where Americans abroad are duped and tortured for being stupid, naive, or just plaine rude. In post-9/11 horror there’s often times no reason for the horror, like in The Strangers. Just random, cruel violence. How much of this was an attitude shift after 9/11 or the result of our own actions in places like Abu Ghraib or the dozen black sites around the globe is an open question. Are we feeling pain or alluding to our own guilt for causing so much of it?

What are some examples of the 9/11 aesthetic in Sci Fi. And do films that appropriate the terrible images of the day comment on the political and ideological fallout?

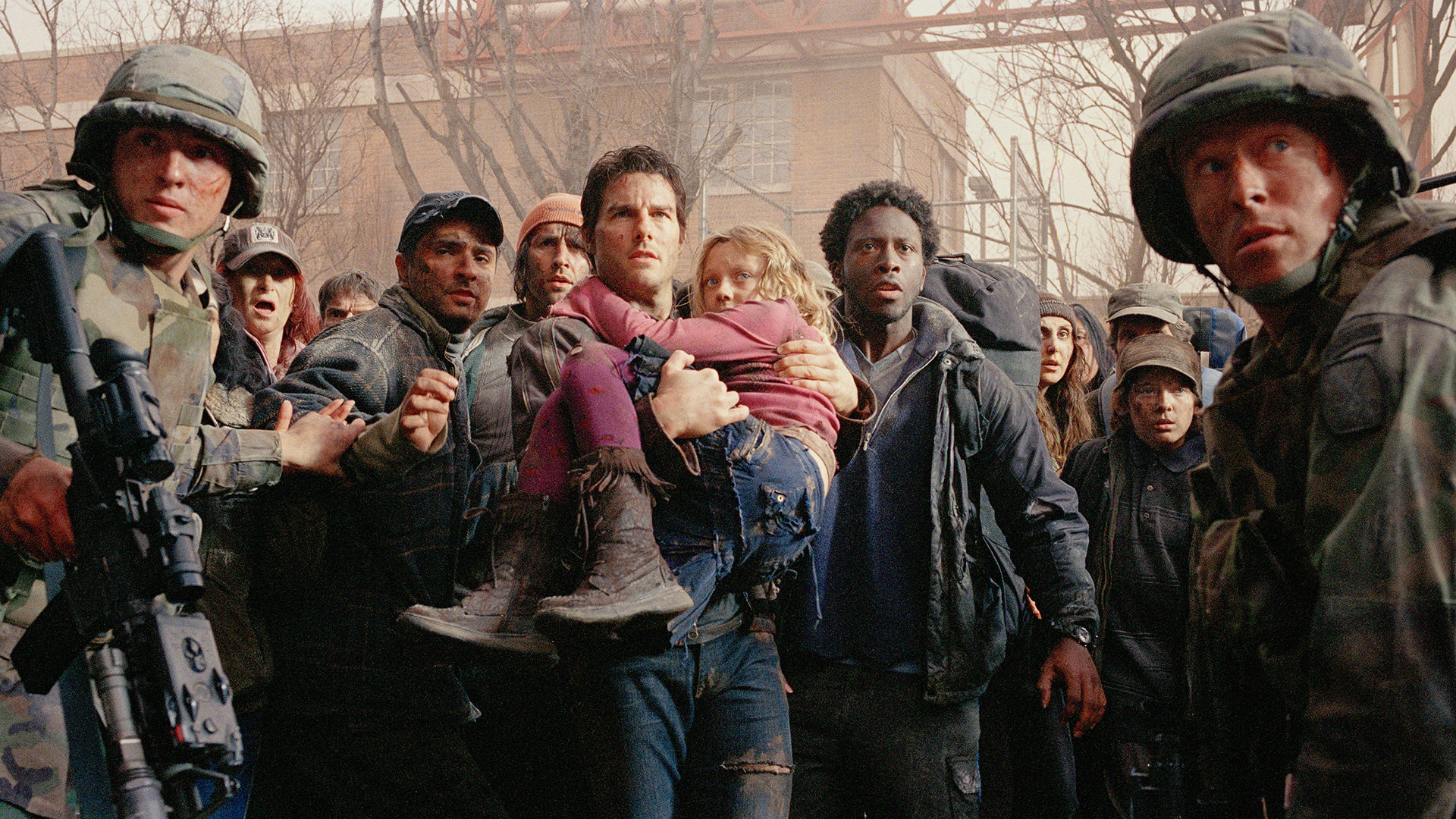

War of the Worlds (2005), directed by Steven Spielberg and based on the 1898 novel by H.G. Wells. The script is written by Josh Freedman and David Koepp. It stars Tom Cruise, a young and from what you can already see here a very talented Dakota Fanning, a memorable appearance by Tim Robbins, and a great actor I like, Justin Chatwin. He was in a few seasons of Shameless on Showtime. But, it’s mostly the Cruise and Fanning show as father and daughter make the perilous journey from Bayonne New Jersey to Boston, dodging the fearsome tripods and vampiric alien creatures bent on literally sucking humanity dry. Along the way, human beings prove they can be just as monstrous as the aliens, a trope we all recognize in SciFi.

Spielberg, who released Munich around the same time, another film with very explicit references to 9/11 and the war on terror, wanted audiences to know his new sci fi movie was heavily influenced by 9/11:

“It seemed like the time was right for me as a filmmaker to let the audience experience an alien that is a little less pleasant than E.T. Today, in the shadow of 9/11, I think the film has found a place in society.”

He also said that his film was ‘about Americans fleeing for their lives, being attacked for no reason, having no idea why they are being attacked and who is attacking them’

The film’s references to September 11 are both visual, the most striking and sometimes really disturbing elements, and within the plot, which is of course very familiar but resonates in a specific way in 2005. War and terror are a way of life.

Let’s run down a list of how War of the Worlds does this:

The aliens don’t show up in flying saucers like most alien invasions, they are already here, buried underground and waiting to strike like a well-organized terrorist cell.

The kids’ only frame of reference for what’s happening is terrorism. Fanning shrieks, “is it the terrorists?” Robbie too assumes this, but Ray, who saw the tripod rise and obliterate everything, tells him they’re from somewhere else.

Like 9/11, everyone has to recalibrate their frames of reference.

The most vivid destruction occurs in northern New Jersey. Spielberg did not want to tear apart Manhattan out of respect it seems, but these communities in NJ were greatly affected by 9/11. As we’ve seen in other films, this is where many of the people who died, the commuters, came from.

The plane crash, with a fiery 747 engine literally in the living room where the TV would be is a nice touch, and scary. We are meant to think a tripod is coming, but worse, it’s a plane.

Robbie, Cruise’s son, has a very specific paper assignment to work on during this weekend with his estranged father. The French Occupation of Algeria. Combine that with the extended scenes in rural New England and the conclusion and Boston and there is a prominent revolution and resistance theme going on here. . We see this in many other Sci Fi examples, from Battlestar Galactica to the series Falling Skies, another story of alien invasion in and around New England.

This is most dramatically portrayed by the strange Tim Robbins character, another survivor hiding in the basement of an old farmhouse. He’s frantic and unstable, trying to enlist Ray in a crazy dream of insurgency. “They defeated the greatest power in the world in a couple of days.” Robbins wants to be like the Iraqi insurgents, picking off the vastly superior enemy one by one. As if it wasn’t obvious enough, Robbins tells Ray, “Occupations always fail. History’s taught us that a thousand times.”

Here’s Ray and Robbins having it out after watching the tripods feed on human beings, prompting Ray to kill Robbins, but not before he paints his picture of an underground army waiting to topple the alien overlords.

Smaller moments, like the blood bank saying “we already have more than we need.” Everyone, including me, seemed to think giving blood was the best way to help after 9/11 and all it did was burden the hospitals and blood banks. This is a nod to that.

Cloverfield (2008), directed by Matt Reeves and written by Drew Goddard. It’s part of the Bad Robot, JJ Abrams universe and you might remember the novel advertising campaign which capitalized on the viral trailer idea. The mystery behind Cloverfield, which was just a government codename, had everyone buzzing. This 88 minute movie comprised totally of simulated “found footage” has no real stars, although I recognized Lizzy Caplan from Masters of Sex and TJ Miller from Silicon Valley. The star is the titular character, a Godzilla-like monster that shows up out of nowhere and tears Manhattan apart. Cloverfield tears the head off of the Statue of Liberty and demolishes the Brooklyn Bridge

There are some stunning scenes that mimic now iconic 9/11 footage. Straggling zombie NEw Yorkers in shock, covered in dust, papers falling from the sky. The Empire State Building collapses just like Tower 1. A lot of people were offended by Cloverfield for cynically appropriating these moments. Not everyone, however. Jessica Wakeman at the Huffington Post, only 17 on 9/11 had this to say:

“The first 45 minutes of Cloverfield is the closest I think I can get to showing someone else what 9/11 was like for me on an emotional level. Cloverfield nails what that morning felt like: the confusion at first, and then fear overwhelms and all you can think about is the possibility of dying and needing to escape by getting out-out-out but where can you go because the subways and trains aren’t running? It gets what it looks like and feels like to believe there’s 8 planes in the air, that the president ordered any non-grounded aircraft to be shot down, they could be shot down above your city and kill you, and what if there’s a ground attack? It depicts what it’s like to be convinced that that day is the day you are going to die. You are 17 years old and you are going to die on a sunny Tuesday morning in the middle of New York City.”

Falling Skies (2011-2016) on TNT, starring Noah Wyle. This is another alien invasion story not unlike War of the Worlds, but this time the occupation sticks and humanity gets to form the resistance army Tim Robbins spoke about. The five seasons follow the human resistance army as they organize and win back humanity’s freedom.

Aside from 9/11 like imagery of destruction, the theme of resistance and insurgency is foregrounded here. The American Revolution is all over Falling Skies and Noah Wyle is a military history professor who uses those lessons to wage war against a vastly superior enemy. He counsels his band of citizen soldiers to remember the Minutemen, partisans throughout history, but not obvious examples like Vietnam or anything suggesting American weakness. Steffen Hantke wrote a great article about Falling Skies as a reflection of Tea Party ideology, a fantasy where citizen militias reise up and destroy the alien occupiers of urban environments. Anti-Obama Sci Fi

In Falling Skies and the USA series Colony, humans are like the Fedayeen fighters in Iraq, attaching machine guns to pick up trucks, planting IEDs at the side of the road. They wear ratty clothes, live hand to mouth, and speak of destroying the foreign invaders and purifying civilization.

Here’s Wyle addressing his battle hardened militia, urging them to be brutal.

What do we make of so many post-9/11 Sci Fi films and series about resistance? None seem self-aware enough to note that by 2003 it is the US that is showing up uninvited and destroying cities and infrastructure, provoking the creation of armed resistance. HG Wells wrote War of the Worlds to critique British imperialism, to highlight how regarding other cultures like they were insects was inhumane. What if it happens to us one day? This lesson seems lost on us.

Battlestar Galactica (2003-2008)

The Sci-Fi Channel’s reimagination of the original Battlestar Galactica (BSG) series (1978-79) in the early 2000s earned critical praise and a passionate fan base by addressing critical issues of the day, specifically terrorism and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. BSG blends elements of the classic space opera with timely commentary on racism, religious intolerance and extremism, and humanity’s fraught relationship with technology. “The Cylons were created by man,” the series’ opening text reads, “They were created to make life easier on the twelve colonies. And then the day came when the Cylons decided to kill their masters.

After a long and bloody struggle an armistice was declared. The Cylons left for another world to call their own.” The armistice abruptly ends when the Cylons infiltrate the colonies’ defense network and launch a coordinated nuclear attack on every human settlement and military installation, leaving only the antiquated Battlestar Galactica and a collection of random ships stranded in space. The 2003 miniseries introduces the characters and their complicated personal relationships with each other during intense and unrelenting stress and trauma. Bill Adama (Edward James Olmos), quietly hoping to end his career with Galactica’s decommissioning ceremony on the day of the attack, is thrust into the position of saving what’s left of the human race while overseeing a cantankerous crew filled with drunks and insubordinate pilots, including his estranged son Lee (Jamie Bamber). Moreover, Adama must defer to the lowly Secretary of Education Laura Roslin (Mary McDonnell), the sole survivor in the cabinet and therefore newly inaugurated President of the Colonies. The two reluctant leaders navigate the hazards of civil-military relations during an unprecedented emergency.

The Cylons, no longer just a clunky race of metal Centurions with roving red eyes and metallic voices, are led by intricate “skin jobs” who appear human, practice monotheism (the humans are polytheists), and rule by consensus. For the next several years the two races will try to destroy each other while seeking the fabled home of the Thirteenth Tribe of Kobol – the planet Earth.

Coming just two years after 9/11, BSG is clearly influenced by the event and the wars that soon followed. The Cylon attack is a 9/11, complete with infiltrators, total surprise, and a government leadership scattered and unclear how to respond. In the first episode, Bill Adama gives a heartfelt speech that is ostensibly about his own guilt for his son’s death in pilot training, but it really winds up being the overall theme of the series:

Many of the films we covered this season ask some of the same questions – why are we the good guys? There are other obvious signs, like the wall of the missing, the blighted urban landscape of New Caprica, the stand-in for New York, and just persistent feelings of dread and anxiety about when and where the next attack will be. Once the Cylons are revealed to be humanoids the colonists descend into paranoia and what might be called speciesism.

BSG’s most controversial storyline concerns the Cylon occupation of New Caprica, a failing colony populated by fleet members exhausted by the failed search for Earth. Critics noted references to the American occupation of Iraq, including a violent insurgency and ruthless counterinsurgency, terrorist attacks, the use of torture, and a puppet government. In other words, the Americans are the Cylons and the Iraqis are the “good guys.” Ronald Moore responded to the outcry:

A lot of people have asked me if the Cylon occupation was our way of addressing the situation in Iraq, but it really wasn’t . . . . There are obvious parallels, but the truth is when we talked about the episodes in the writers’ room we talked more about Vichy France, Vietnam, the West Bank, and various other occupations; we even talked about what happened when the Romans were occupying Gaul.

I can see the wink and the nod here, because, make no mistake, the parallels were explicit and incredibly timely.

We talked about Sci Fi that evoked the imagery of 9/11 and Sci Fi obsessed with resistance and revolution. What about the emotional and psychological fallout? The loss, the grief, the shock, the anger, the sense that nothing could ever be the same. One show we both love does all of this very well. HBO’s The Leftovers (2014-2017), based on the novel by Tom Perrotta, was adapted for HBO by Perotta and Damon Lindelof, creator of Lost and Watchmen among others.

The Leftovers presents a universe in which God is dead. One October 14 in the twenty-first century 140 million people world-wide suddenly disappeared – babies, the elderly, the pope, Gary Busey, four out of the five cast members of Perfect Strangers (1986-93), even fetuses in the womb. The shock, horror and trauma of what became known as the Sudden Departure left no one untouched, sending survivors into their own spiral of guilt, self-incrimination, anger, hedonism, and feckless search for answers. Some believe it was the Rapture, while others, especially the faithful, argue the opposite.

As Sophie Gilbert notes in The Atlantic, “the question that Perotta and Lindelof seem to be occupying themselves with isn’t how it happened so much as what happens next? How does humanity respond to a universe in which everything is meaningless?” Initially set in a fictional New York suburb called Mapelton, The Leftovers revolves around the family of police chief Kevin Garvey (Justin Theroux) and Nora Durst (Carrie Coon), a woman who lost her husband and both children in the Sudden Departure. Nora’s brother Matt Jamison (Christopher Eccleston) is a pastor who spends his days revealing the sordid pasts of those who departed to disprove the notion the event was the Rapture.

Garvey’s family is still on Earth, but they are lost to him. His wife Laurie (Amy Brenneman), who lost a pregnancy in the Sudden Departure, joins a cult called The Guilty Remnant (GR) founded by Laurie’s former psychiatric patient Patti Levin (Ann Dowd). Kevin’s son Tom (Chris Zylka) follows a mystic named Holy Wayne (Paterson Joseph) who supposedly takes people’s pain away with a simple embrace. Garvey’s teen-age daughter Jill (Margaret Qualley) lives at home with Kevin, but she’s as cold and distant as the departed. Kevin’s father, Kevin Sr. (Scott Glenn), resides in an insane asylum and pushes Jr. to stop pretending nothing happened and embrace his yet undetermined role in the mystery of the Sudden Departure. Seasons two and three center on Kevin’s path of self-discovery and his relationship with Nora amid the continuing mystery of the Sudden Departure.

Tom Perotta wrote the novel to explore the post-9/11 universe. The Sudden Departure was 9/11 and everything that happens afterwards relates back to this inexplicable trauma. The series expands the universe of the novel, but the themes are preserved. What are some of the obvious nods to 9/11?

First, the date. October 14, the name of the pilot episode, is the date of the Sudden Departure and every season hinges on this anniversary. It’s what everyone talks about.

There is a newly created Department of Sudden Departure akin to DHS, chasing its own tail and never really accomplishing its stated missions. Law enforcement is empowered to take out any and all threats, cults, whomever. The new laws after October 14 were a Patriot Act on steroids.

The series revolves around empty memorials – parades, statues of babies floating up to the sky, the sort of occasions we did not think were so empty after 9/11 because we knew what happened and why. That’s not the case in the Leftovers.

Season one takes place in a suburban NY town like that affected most by 9/11 commuters no longer there. Season one is closest to the novel, so it makes sense.

The Leftovers is about coming to grips with unimaginable grief and processing trauma, and ultimately realizing sometimes you can’t. This is why I chose The Leftovers to write about in my book on Holocaust representation, specifically how Holocaust survivors are portrayed in film. It’s a perfect example of the “before” and “after” idea. The characters in The Leftovers are all just trying to exist.

Two representative clips about this desperate search for salvation from grief.